Sly foxes and copycats. It seems that Australia’s predators, including feral cats, foxes and dingoes, are living up to their idioms by capitalising on human-made roads for hunting. Furthermore, roads and other linear infrastructure dramatically affect how water moves across the landscape and make up the majority of the direct impact of mining activities.

Dr Keren Raiter of the University of Western Australia, the ARC Centre of Excellence for Environmental Decisions, and CSIRO, has been leading research to improve scientific understanding of the cumulative environmental research impact of the global proliferation of roads on predator species’ activity and hydrology.

Keren’s research has found that the activity of Australia’s key predators — cats, foxes and dingos — is up to 261 times greater on human-made roads.

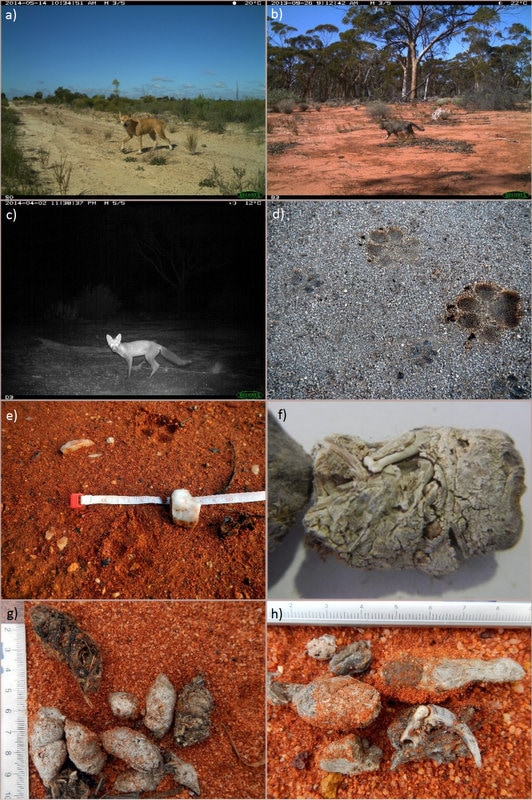

Keren and her colleagues conducted their research at TERN’s research SuperSite in Western Australia’s Great Western Woodlands. The team set motion-sensor cameras and conducted field surveys in and around the SuperSite to compare dingo, fox and feral cat activity on unsealed vehicle tracks and up to three kilometres away; they also assessed hydrological impacts along ephemeral streamlines and in the wider landscape, and conducted an extensive spatial analysis using high-resolution aerial images.

“While people generally tend to think of the impact of mining activity as being focused in and around the mine site, especially the mine pit; spare a thought for all of the access roads, exploration lines, railways, and other linear infrastructure that together account for the vast majority of the mining footprint”, says Keren.

“However, most of the impact of roads is not well understood. We observed predator activity between 12 and 261 times more frequently on roads compared with off-road for all species studied. Predator activity up to 2.5 km away from roads was also affected and even poorly formed and abandoned roads concentrated predator activity.”

In addition, Keren and her colleagues found that linear infrastructure dramatically impacts the flow and distribution of water. The vast majority of ephemeral streams crossed by roads and other linear infrastructure are impacted by channelisation, flow impedance and flow diversion, while erosion and pooling are more than five times as likely to occur along linear infrastructure, than away from it.

Ramifications for conservation

Keren says that the results offer many learnings for nature protection, species conservation, invasive predator control, impact mitigation, and monitoring programs.

“For example, where conservation of a prey species requires predator control, rehabilitating roads in that area may be a more effective long-term strategy than baiting it. Where invasive predators in an area are found to frequent roads, control efforts could be optimised by targeting roads.”

“Also, monitoring approaches and management decisions based on studies that focus monitoring on or near roads should consider that those studies may present an unrepresentative picture of animal activity.”

There is also considerable scope for using these insights to avoid, manage and reduce the effects of roads and other linear infrastructure on hydrological flows, including with hydrologically considerate road design.

Better development approvals and road planning around the globe

These findings, have important implications for development approvals and road planning in Australia and around the globe.

“Impact assessments pertaining to the construction of roads or other linear infrastructure should account for the effects of roads on predator activity, as well as the many other ecological impacts that tend to fly under the impact assessment radar,” says Keren.

“Options for mitigating impacts of roads include avoiding the creation of new roads in intact landscapes, careful consideration of routing for roads that cannot be avoided, and committing to timely rehabilitation of roads that are no longer needed and, to maintain large trackless areas where possible.”

To make such development decisions and mitigation action planning easier, Keren and her colleagues have come up with a framework that ensure all ecological impacts, including the enigmatic ones, are considered and addressed.

“With a little extra consideration, there is substantial scope for mitigating the ecological impacts of existing and planned infrastructure developments.”

“It’s not just foxes who can be the sly ones, humans too must get smarter. We have the tools and now it’s time to use them.”

- Read more on this research using TERN in these journals: Trends in Ecology and Evolution; Landscape Ecology; Journal of Environmental Management; and Biological Conservation.

- Click here for more information on TERN’s Great Western Woodlands SuperSite and how you can use the research infrastructure at the site.