In March we’re featuring Griffith University’s Environmental Futures Research Institute and research that’s developing solutions to facilitate clean, resilient and sustainable futures, and improved health and wellbeing of people.

The Environmental Futures Research Institute (EFRI) combines science, innovation and local Australian experience to expand new knowledge through fundamental research. The Institute hosts around 250 researchers, including academics, research-only staff, associates, adjuncts, visiting researchers and more than 120 PhD scholars.

Exploring new science frontiers, stimulating innovation and influencing public policy, EFRI members develop solutions that facilitate clean, resilient and sustainable futures, and continue to improve the health and wellbeing of people.

“Our research addresses key environmental priorities that reflect critical global issues and identifies niche markets and research gaps in the current marketplace.”

Dian Riseley, Institute Manager, EFRI

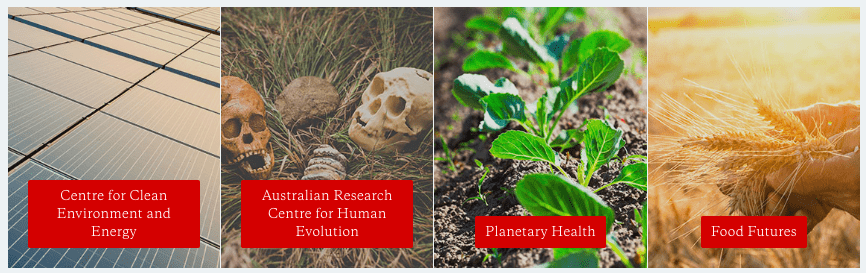

EFRI has four key areas of research: 1) environment and energy; 2) human evolution; 3) planetary health; and 4) food futures.

Predicting animal to human virus transmission risk periods

The Wildlife Disease Ecology Group sits within the Institute’s Planetary Health research platform. Its research aims to develop a better understanding of the dynamics of wildlife diseases which can be used to ensure scientifically sound decisions relating to the health of wildlife, domestic animals and people, as well as conservation.

Dr Alison Peel is a veterinarian and wildlife disease ecologist with the group who is researching the dynamics and drivers of infectious disease, particularly in bats. Her research focuses on Hendra virus and flying fox ecology in Australia and is being used as a template for other bat-borne viruses in other parts of the world.

“All animals and people can carry a range of different viruses that don’t cause illness in the main host species, but can be fatal if they transmit to other species. Hendra virus in flying foxes is an example, which can be fatal when it ‘spills over’ into horses and people. We think that land clearing and climatic conditions are driving this spillover.”

“We work closely with the Government and notify them of when our results indicate upcoming periods with an elevated risk of transmission.”

Alison Peel, EFRI Planetary Health research platform

The importance of Dr Peel’s research is paramount when you consider that bats have also been implicated in the transmission of coronaviruses and Ebola to people—again, potentially as a result of human disruption to natural environments.

By identifying high disease transmission risk periods and understanding the underlying environmental drivers, this research may lead to larger, sustainable win-win solutions for human health and the environment at the global scale.

Native bees stepping up to the plate

At EFRI’s Food Futures research group, Professor Helen Wallace is also conducting topical, globally applicable research into the increasing role native bees could play as agricultural crop pollinators if the European honeybee population collapses.

“Australia’s native stingless bees could be a key line of defence for the nation’s horticulture industry against the devastating bee parasite Varroa destructor, a mite which is predicted to enter Australia in the coming years and could cost the industry over a billion dollars.”

“Stingless bees are not targeted by the mite and are used successfully to pollinate some commercial species of fruit and nuts, such as macadamias, but their effectiveness as pollinators for a range of other plants remains uncertain.”

“We know that stingless bees visit flowers, but are they efficient pollinators? Do they track the pollen to the places it needs to go? Now we need to find out.”

Helen Wallace, EFRI Food Futures research platform

The project will compile ecosystem data and review existing evidence on the potential of stingless bees and carry out studies on a range of fruit and vegetable crops, testing first if the bees visit the flowers and transport the crop pollen.

Species diversity as predictors of environmental change

Collaborative research is a key theme at EFRI, says the Institute’s Dr Paul Oliver who holds a joint academic appointment as a curator in the Queensland Museum’s Biodiversity Program.

Dr Oliver has participated in expeditions to some of Australasia’s most remote areas, described over 50 new species, and documented completely novel hotspots of biodiversity. In 2019 he described three new frog species and a colourful new gecko from Papua New Guinea’s mountain forests.

“Looking into patterns of genetic diversity within and between species helps us understand how past environmental changes have affected the region’s diverse fauna and flora.

We are particularly interested in relic species and populations—animals that formerly had much wider ranges—they provide a powerful tool for predicting how sensitive organisms may be to effects of future climatic change.”

Paul Oliver, EFRI and the Queensland Museum

Long-nosed Tree Frog (Litoria sp nov) (Credit: Tim Laman, National Geographic)