As any good grazier will tell you, you can’t look after your livestock properly unless you also look after what they eat.

In Australia, that mostly means looking after native vegetation. Livestock grazing is a big industry – the highest-value sector in farm production, with beef production alone bringing nearly $7,300 million a year to the national economy.

Grazing for meat production occurs over about half of the land mass of the country, mostly on five vegetation types: acacia woodlands with saltbushes and other chenopods; spinifex and other hummock grasslands of desert Australia; Mitchell grass downs and other tussock grasslands; tropical savannas; and eucalypt woodlands.

TERN facilities operate in all these ecosystems. Some are working collaboratively with land managers to learn from them and to supplement landholders’ knowledge. Ecologists studying the semi-arid and arid lands recognise that landholders, collectively, have a wealth of knowledge and experience about their country, sometimes going back generations. They can provide potentially valuable data on vegetation and soils, because 91% of Australian landholders who graze livestock monitor to varying degrees the condition of their vegetation and soils, and a third of these have set targets to maintain minimum amounts of ground cover for feed and regeneration, but also to protect fragile soils. They observe pasture yields, the composition of plant communities (and which plants stock prefer), and the prevalence of weeds.

Land managers use the information to manage total grazing pressure: not just the numbers and movement of livestock, but the numbers of all other herbivores, too, especially kangaroos and other macropods, and feral animals, especially rabbits, camels, goats and donkeys. Maintaining healthy pastures is particularly important in the environment of arid Australia, which is characterised by boom–bust cycles.

As well as their own monitoring, landholders have many sources of information, most of it based on science, from Bureau of Meteorology reporting, to scientific research synthesised by such diverse organisations as Meat and Livestock Australia and the Australian Collaborative Rangelands Information Centre (ACRIS).

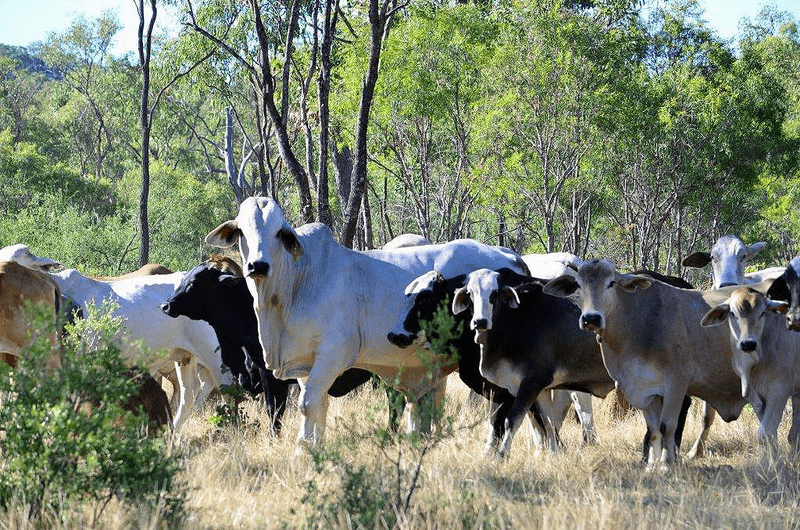

Cattle grazing tussock grasses at sunset in the Victoria River District of the Northern Territory. The area has moderate tree cover making it difficult to delineate between tussock grasslands and tropical savannas (photo courtesy of Andrew White).

Our recently published book, Biodiversity and environmental change: monitoring, challenges and direction describes several long-term research projects that have made a qualitative difference to our knowledge of how semi-arid and arid native vegetation systems function. Much of the research has been focused on production. Some of the results of these studies are summarised below.

At Toorak Research Station, near Julia Creek in north-western Queensland, 26 years of monitoring showed up the short-comings of short-term monitoring. Early results seemed to suggest that Mitchell grass could withstand heavy grazing of up to 80%, but continued monitoring showed that this was the wrong conclusion to draw. In fact, the grass did succumb to such intense grazing, but it responded slowly, and the decline only became apparent with long-term monitoring. It took 26 years for scientists and graziers to be certain that by limiting grazing to 30% of the pasture, graziers got good economic returns and the Mitchell grass continued to thrive, and to complete its long life cycle, which is at least 26 years. It also became clear that the grass thrives better when it’s grazed.

This is interesting research which is specific to this ecosystem. These findings highlight the important need for ecosystem-specific research, as other research in our book in different ecosystems, such as woodlands and the alpine region, illustrate the damage that can be caused by high-intensity domestic livestock grazing.

Analysis of 14 years of data collected in the Kimberley under the Western Australian Rangeland Monitoring System (WARMS) has given us a detailed picture on plant-species composition of 13 types of tussock grasslands, and shows how grazing livestock have changed these over time.

The South Australian Government attributes the success of its Bounceback program, to control feral herbivores and improve biodiversity health, to the involvement of local traditional custodians and graziers. The data indicate that livestock grazing seems to have little impact on the number of species in chenopod shrublands, although the number of native animals was greater in ungrazed sites. The research also showed that rainfall had the biggest impact.

Despite the overall production focus, some projects have a stronger ecological focus. At Koonamore, in South Australia, the effects of grazing (and its cessation) on saltbush vegetation have been monitored for nearly 90 years, making it one of the longest-running vegetation-monitoring projects in the world.

Some data are also available on the interaction between production animals and native fauna and flora, due to long-running ecological research conducted by LTERN’s Desert Ecology Plot Network.

But there remains a wide gap in knowledge on biodiversity in all kinds of grazing lands. Now several TERN facilities – the SuperSite at Calperum Mallee, AusPlots Rangelands, and the transects of the Australian Transect Network – are beginning to provide data and analysis that will help us understand how productive and native aspects of inland ecosystems can function harmoniously.

Cattle grazing in rangelands (photo courtesy of Gavan Nolan, KordaMentha)

Published in TERN’s Environment Monitoring newsletter February 2014