Forget the workplace discussions happening around the water cooler: at the symposium they were around the computer terminals set up to spotlight the various facilities’ data portals.

Because of the importance of the data portals to TERN’s ability to deliver its products, an afternoon of the program was dedicated to free discussion about the portals, and in a plenary session, the facilities also gave progress reports on their data delivery infrastructure.

Introducing the session, the TERN Director, Professor Tim Clancy, noted that the facilities were beginning to position themselves to be influential players in the political and environmental landscape of the future. By providing a means for scientists to store, share, search and integrate data in a manner that directly cites the data provider, they are an essential stepping stone to open data and open publishing, and a cornerstone for integrative, multi-disciplinary science required to understand and manage Australian ecosystems. They are building new capabilities in Australian ecosystem science, and are at the cutting edge of expertise or technology in some areas.

TERN data-discovery portal

The TERN data-discovery portal is a gateway to the environment database held across all the TERN facilities, and would be set up to guide users to the data they want.

The development of the portal is coordinated by Dr Siddeswara Guru, who is based at TERN Central.

‘We’re really just a relay. Our role is to help people find the data, understand how it is to be used, and get to it quickly,’ Guru said. ‘So they can do this, we have to write a single metadata standard that can accommodate all the data held in TERN facility portals.’

TERN was set up to build on the strength of existing data collection networks and enable them to be joined with new systems in a network of data portals, and the TERN portal was the entry to data from the broad diversity of ecosystem data collected for Australia. Building TERN on the backbone of existing ecosystem science communities was critical for the longer-term viability of this system.

‘The TERN data-discovery portal will be used by ecosystem scientists, by policy makers and managers from local councils, state government and the commonwealth, by environmental management organisations, by citizen scientists, and schools, so we have to make it easy to use for all these types of people,’ Guru said.

He said metadata harvesting from the TERN facilities had begun.

‘We have harvested close to 450 records from four facilities so far, and expect to have metadata records from all TERN facilities by the end of the year,’ Guru said. ‘You can understand that this is quite a big job, as all the TERN facilities publish data from different ecosystem science domains, and from the past as well as the present.’

The beta release of the portal is expected in June. The portal will be hosted by the Queensland Cyber Infrastructure Foundation (QCIF).

AusCover

Introducing the capability of AusCover, facility director Dr Alex Held talked about the difficulties of unlocking the information stored in archives of data collected 30 years ago, before current technology was even imagined, in ways that makes it useful in measuring changes in Australian environments.

‘To do this we are working in three major infrastructure areas: hardware; software; and people and datasets to underpin data storage, access and validation,’ Alex said.

‘You will be able to go into the individual pixels that make up a satellite image and look over time to extract data, to look at the impacts of difference climatic events from year to year and to build a longer-term picture. AusCover is now established as an indispensible data source. We will eventually have close to 50 different satellite-derived datasets available for use by all. Partly as a result of our work at AusCover, the global community sees Australia as a lab for validating datasets,’ Alex reported.

The presentation has several hyperlinks to AusCover web pages.

OzFlux

Dr Peter Isaac described some of the difficulties the OzFlux team has overcome in developing its data delivery system — and flagged the successes that would begin to occur as users started pulling together data from remote sensing, the flux tower network, field research and the use of models.

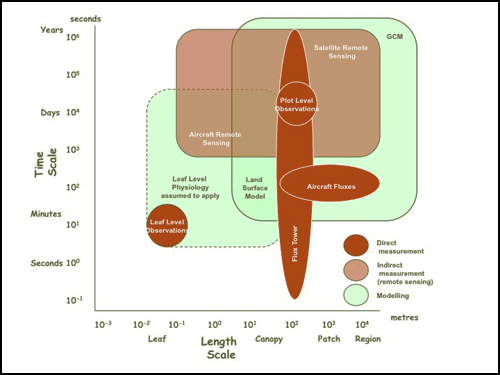

‘We’re dealing with ecosystems across Australia that differ by degrees of magnitude in carbon uptake and spatial variability. Different measurement techniques cover different ranges of spatial and temporal scales. Overlap in measurement scales is often small or non-existent. Where there is overlap, there is often a difference in the observations; for example, flux towers measure the exchanges directly, while remote sensing measures radiances from which we try to infer the exchanges. We have good temporal coverage, but limited spatial coverage – and to remedy that we’re working with AusCover,’ Peter said.

‘However, we are starting to record the heartbeat of ecosystems as they respond [to stimulus] – pulses of water vapour and carbon uptake, that we can match to hours of sunlight,’ he said.

The OzFlux portal has been operating for 18 months. Originally a Monash University initiative, it has now expanded under TERN.

‘Two years ago, our central repository for flux data did not exist. Now we have one. We’ve had a high uptake by the OzFlux community. We have 62 registered users, 16 in Australia and the rest international organisations,’ Peter said.

OzFlux had 19 collections available on the portal, totalling 46 site-years of data.

Diagrammatic representation of the time and space scales at which OzFlux works

Eco-informatics

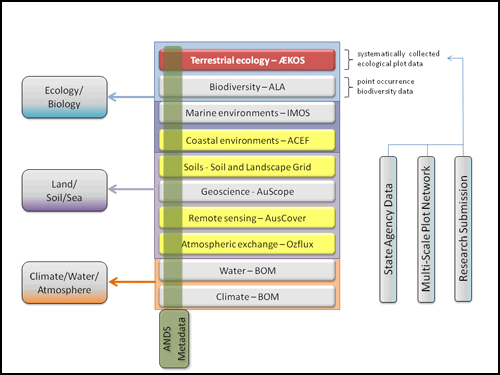

The Director of Eco-informatics, Mr Craig Walker, described the role of the facility’s portal, part of a solution called ÆKOS (Australian Ecological Knowledge and Observation System), as the means of bringing together in a single point of access the existing ecological data of state and territory agencies involved in environmental and land management and also plot data from researchers in the Multi-Scale Plot Network facility.

‘To give you one example, South Australia’s Department of Environment and Natural Resources has estimated that the data contained in their biological databases cost $153 million to collect and store. Bringing all this data together from the states and territories into ÆKOS is making better use of a massive investment,’ Craig said.

One of the challenges Eco-informatics is solving is how to make plot data re-usable. He explained that, because raw ecological plot data collected for a specific purpose, unless the context for collecting the data was understood researchers could not assess whether existing data was suitable, and might collect their own rather than use someone else’s.

‘What we’re building is the first of its kind: up till now, ecological plot-based data has not been able to be stored or made available with its full richness. But the portal is intended to deliver this complexity in an easily accessible way. Eco-informatics released an alpha (or preliminary) version of ÆKOS last October and based on user feedback, has now started work on a beta version for release later this year, and the release of a final public version in 2013.’

Eco-informatics sees ÆKOS (coloured red) filling a national gap for complex plot-based data

in the landscape of environmental information in Australia

The plot facilities

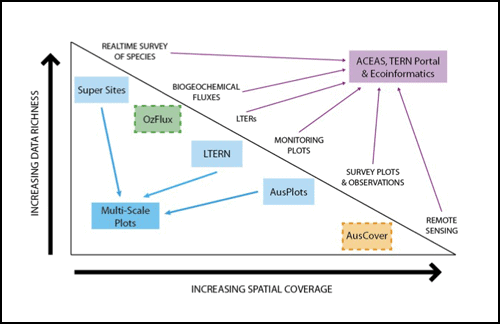

By integrating its work across the several plot systems in TERN, the Multi-Scale Plot Network (MSPN) is working across a hierarchy of spatial and temporal scale to provide a richness of data that would be delivered through ÆKOS and the supersite portal.

The plot network encompasses AusPlots, which provides baseline assessment of flora and fauna at a large number of very small sites (i.e. less than 10m); LTERN, which links collections of larger plots over long gradients and was used to measure flora and fauna numbers and dimensions; and the Australian Supersite Network, which assesses flora and fauna along with biogeochemical processes at key sites. The MSPN coordinator, Dr Nikki Thurgate, said that, whatever the scale of the plot, increasing data richness changed the way people looked at the environments they were studying.

‘MSPN is trying to tell an Australian ecological story through space and time; we’re looking at where things are going, rather than providing snapshots of where they are now,’ Nikki said.

‘We can increase the power of the data we collect because it can be used in wider ways, in new ways, including in management and policy, because what we are doing will help us – scientists, government and land managers – understand the implications of different land-management decisions. We have gaps at the moment, where we can’t tell a story. One of the questions we’re looking into is where we move in future, so we can tell this story.’

As with all the TERN facilities, MSPN data would find a use not just among TERN facilities – ACEAS, e-MAST, AusCover, OzFlux and Soils – but also with researchers, the Australian Government (e.g. as part of state-of-the-environment reporting), state governments (e.g. in monitoring change) and natural resource managers.

‘Because our data will be integrated through ÆKOS and the supersite portal, most people won’t even know they’re using MSPN data,’ Nikki said.

Ms Michelle Gane, who works on the south-east Queensland supersite through the Institute of Sustainable Resources at the Queensland University of Technology, reported on progress in the supersite network.

She said metadata was fed to ÆKOS and to the TERN portal, and linked to the ANDS research discovery site. Links were also being made to repositories with OzFlux and Coasts, and would be developed with AusCover and ÆKOS.

‘The supersite portal emphasises multi-disciplinary research. We’re already building links with the Data Observation Network for Earth (DataONE), and the US National Science Foundation-funded DataNet infrastructure. As well as being compatible with international data systems, we are creating a standardised interface for the ecosystem community that allows people to deposit TERN and contextual datasets,’ Michelle said.

While use of the portal had remained steady over the past six months, the team was starting to see an increase in numbers of downloads. The next steps were to create a researcher community to get datasets into the repository, and to see them being used.

‘This is a people process, not a data process, so we’re using Facebook as a space where people can discuss datasets. We’re also coordinating with MSPN communications, because MSPN is working well and, as much as possible, we embed one thing inside another,’ Michelle said.

Representation of the spatial and information depth captured by MPSN

Coasts

The Australian Coastal Ecosystems Facility has three objectives to deliver its data, which are similar to those of many of the TERN facilities:

- to establish a coastal community of practice to identify the most important coastal datasets, and improve the technologies that underpin data analysis

- identify the national datasets that need to be collected, and fund research to fill gaps

- improve digital access to observational data, and provide methods for it to be analysed and visualised.

The Director of the facility, Dr Andy Steven, said that, like other data repositories in TERN, the coastal portal contained a variety of information types – on water quality, wildlife, fisheries bycatch, biogeochemistry (the study of the chemical, physical, geological and biological processes in the natural environment), topography and bathymetry, landform processes, and wave and shoreline analysis.

‘This is about much more than just data. It’s also about linking otherwise separate datasets, helping natural resource managers, planners and developers make better decisions, and creating collaborations of coastal researchers,’ Andy said.

‘Our key tasks are the ongoing development of the web portal to upload more datasets and prepare metadata for them. We are also looking at the curation of the datasets.’

Soils

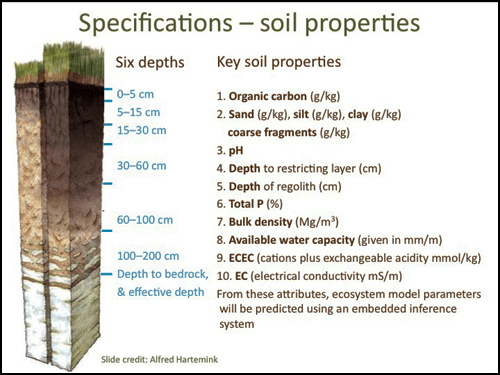

The soils facility is reframing the way in which soils data is made available. The result will be a much more sophisticated way of showing soil information, including variability, in three dimensions and over time.

Facility Director Mr Mike Grundy said that, to provide the data needed to understand ecosystems and climate change, the facility needed to refocus soil science, from mapping soils to understanding the function of different soils.

‘This will give us a new set of landscape descriptors that will integrate with earth observations, climate biogeochemical models, and monitoring systems. Our information will reduce the level of uncertainty that exists in current models, and we’ll be able to see the land with a degree of refinement that hasn’t been possible before,’ Mike said.

In its first stage, the facility would establish the main features of the soils grid, including the ability to provide information at scales needed to understand and make management decisions about ecosystem processes. In the second stage, the team would cast a wider net, to capture more types of source data and soil attributes.

‘Some of the data products we will produce are much more comprehensive than anything we’ve ever produced before; for example, 100m soil grid data across Australia, and 30m soil grid data of important landscape descriptors,’ Mike said.

The team anticipated that data delivery would be operating fully by June 2014.

The facility’s infrastructure will allow it to take data from different depths and for different

attributes of soil to create an understanding of how soils function

e-MAST

The Ecosystem Modelling and Scaling Infrastructure (e-MAST) facility will be principally occupied with putting data to work, rather than collecting it or facilitating its redistribution.

Facility Director Professor Colin Prentice said the facility was supporting ecosystem science, impact assessment, and management by:

- developing research infrastructure that could integrate data streams from TERN and elsewhere

- building the capacity to benchmark, evaluate and optimise ecosystem models.

‘Climate change is the elephant in the room. We need to look at it, and ask how it’s changing the rules,’ Colin said.

‘There are other questions we need to ask, and find answers for. How much carbon dioxide is exchanged? How much carbon can be stored, and where? What are the risks of fire? What are the drivers for water use by ecosystems, and for run-off into rivers? These things are not properly quantified across the country. For example, if you have more trees, there is more water stored there, and less in the rivers. There are definitely trade-offs to be made between the ways we use or conserve carbon, water, and biodiversity.’

He said that, among the TERN facilities, e-MAST would particularly help AusCover, OzFlux, all the plots groups, and ÆKOS maximise the use of their data, and that researchers, natural resource managers, conservation organisations, and commonwealth agencies such as the Bureau of Meteorology and the Department of Climate Change would use e-MAST modelling.

‘We want to see a change of culture so that modelling is no longer pursued just by modellers who do nothing but model, but work in collaboration. This means the systemisation of modelling so that it is applied, it has more of a presence, it is firmly rooted in observations, and it can be more easily interrogated.’

ACEAS

The Australian Centre for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (ACEAS) was driven by a desire to see many more interdisciplinary and multi-disciplinary studies of the big questions such as climate change, not just between scientists but also involving land managers and policy makers, the facility’s Program Manager, Associate Professor Alison Specht, told the symposium audience.

‘Our data-delivery infrastructure needs to show the benefits of collaboration, not just between disciplines but including land managers and policy makers as well. We’re beginning to do that: we have a typology of vegetation type and its relationship to fire that is about to be published. That wouldn’t have happened without ACEAS being able to bring people together. And we have a group that, in partnership with ANDS, is developing models of 130 small-mammal populations to predict extinctions. That’s another new understanding,’ Alison said.

‘As well as publishing the results of the working groups we fund, and making sure they are discoverable, we are also helping people to find the right places to store their data. And we are trying to rescue long-term and historic datasets that might otherwise not be conserved, and that is something it is a pleasure to do.’

The facility was beginning to focus on improving cross-TERN analysis and synthesis, and to develop ways of including post-graduate students, supporting other NCRIS facilities, and improving networks with international synthesis centres.

Published in TERN e-Newsletter April 2012