Just like this year, 2013 kicked off with heatwaves that started in Western Australia and swept eastwards across the continent, contributing to Australia’s hottest year on record.

Thanks to TERN’s OzFlux infrastructure, ecosystem observation data now exist to investigate a number of aspects regarding the impact heatwaves have on Australian ecosystems, and a team of researchers is on the case.

While heatwave events are episodic, they can still have significant and mostly negative effects on ecosystems. With global warming leading to higher air temperatures and a probable increase in extreme events, it is likely that ecosystems will be hit by more frequent and more extreme heatwave conditions. The OzFlux team is therefore keen to understand the effects heatwaves have on the energy balance, carbon uptake, water use, and the overall health of Australia’s ecosystems.

Step one is to take a look at the data that several OzFlux towers captured during the heatwaves in January and March 2013 and see what is happening to the ecosystems at the sites.

Dr Lindsay Hutley of Charles Darwin University is part of the preliminary investigative team and says: ‘We are anticipating seeing reduced gross primary productivity (GPP), net ecosystem production (NEP), light-use efficiency (LUE) and water-use efficiency (WUE).’

‘Or, we may even see a limited response across all variables, which would also be of great interest.’

Dr Víctor Resco de Dios of the University of Western Sydney has also started preliminary analyses of the extreme heat events.

‘The heatwaves of 2013 were short-lived, so no dramatic long-lasting effects on net ecosystem exchange (NEE) were apparent,’ Victor says.

‘The soil at our measuring locations was relatively wet, and it seems that no legacy effects were noticeable. It may be just like the Canadian tennis player who passed out at the Australian Open during this year’s heatwave – he was fine afterwards.’

Over the coming year, the team is keen to test the hypothesis that when the ground is relatively wet prior to a heatwave, the vegetation recovers immediately, and that only when the soil is dry is recovery made difficult.

The researchers are also interested in using data from the flux towers to contribute to models such as those being developed by TERN’s eMAST facility and by CSIRO as part of Australia’s new ACCESS weather and climate model. Both are used in landscape management, carbon accounting and climate prediction.

Currently, such models are not able to accurately capture short-lived extreme events, but by accumulating more data about sub-daily ecosystem processes, uniquely captured via flux towers, researchers can dramatically improve model accuracy.

The more flux towers there are, the better will be our capacity to increase the accuracy of predictive models that will assist us in understanding the impacts extreme climatic events have on Australia’s diverse ecosystems.

Bringing these plans to fruition will require a long year of hard work, so stay tuned for more news from TERN’s heatwave team in 2014.

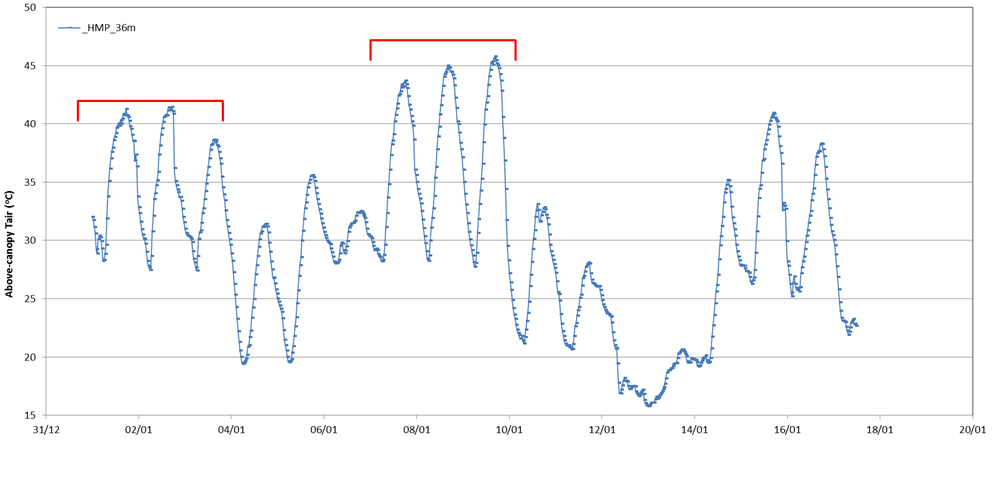

The OzFlux monitoring tower (above) at the Great Western Woodlands SuperSite, Credo Station, WA, captured both meteorological data and the rate of canopy water use and carbon uptake and loss during the heatwaves of January and March 2013. The tower also measured canopy temperature data during the events, capturing two successive three-day heatwaves in January 2013 (data shown below courtesy of Craig Macfarlane, CSIRO). Successive events like these make it harder for ecosystems to cope with such extreme events.

Volunteers caring for dehydrated bats from the #heatwave in #Adelaide @abcnews @abcnewsAdelaide pic.twitter.com/kB4YezbQMC

— Kim Robertson (@KimRobertson4) January 16, 2014

Published in TERN newsletter January 2014