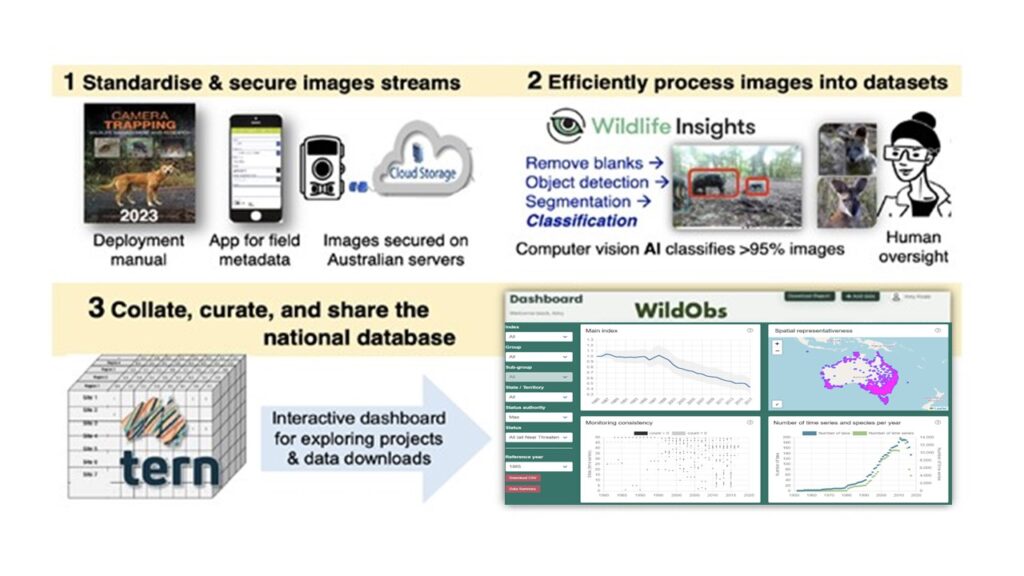

TERN has been supporting wildlife monitoring experts in the launch of WildObs, Australia’s wildlife observatory. WildObs will standardise the collection and processing of data sourced using camera traps, then collate, curate and share the database for research.

Experts call for more wildlife monitoring

Australia is in the midst of a globally-recognised wildlife extinction crisis. A staggering 148 Australian mammal species are listed as extinct or threatened under the Australian Government EPBC Act (Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999). For many other species, we simply do not have sufficient data to establish population trends.

The Australia State of the Environment (SoE) report, released last month, found monitoring of threatened species and communities is mostly inadequate, with 21–46% of threatened vertebrates and 70% of threatened ecological communities not monitored at all. Where monitoring does occur, quality in terms of national extent and adequacy is generally poor (although the report named TERN as a leader in this field, with the most rigorously designed monitoring programs for threatened ecological communities).

Peak bodies such as the Ecological Society of Australia (ESA) have responded to the SoE and detailed key recommendations for policy-makers, decision-makers and land/sea managers to save species and ecosystems and enhance environmental monitoring. Recommendations include increased long-term investment in environmental management, research and monitoring to halt further losses of species and ecosystems. Further investment is recommended for national environmental monitoring programs to leverage existing systems and platforms, assess management effectiveness and inform future programs. To achieve this, data from new and legacy monitoring programs must be FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable).

Camera-traps have many applications

Collecting and analysing data on free-ranging animals is burdensome, and relies substantially on the use of expensive remotely-triggered camera traps. Camera traps are indispensable in field-based discovery research on species abundance, distribution, richness, or behaviour, and are used extensively in applied contexts to test the effectiveness of conservation interventions, manage pest species, track ecosystem responses to threats like climate change, fires, or disease, or to inform and reduce the costs of economic development such as mining.

Overcoming the camera-trapping data deluge

Around 10k cameras are deployed across Australia at any given time, each collecting thousands of images that could, in theory, be used to improve environmental outcomes. In practice, however, camera images are easier to acquire than to process and analyse. A single study may produce millions of images that must be annotated to the level of species or individual—a laborious, expensive process that bottlenecks research and decision-making and suffers high error rates. Camera datasets are also nearly all siloed, off-line and incompatible, creating barriers to collaboration across organisations and preventing powerful cross-site or temporal analyses of population trends.

To address these significant problems, Dr Matthew Luskin at the University of Queensland and colleagues have decided that it is time to establish The Wildlife Observatory of Australia (WildObs) to:

- Standardise ongoing camera deployment and datasets with a protocol manual and smartphone field app to ensure robust sampling and metadata collection across existing and future surveys;

- Mobilise vast troves of existing ‘legacy’ camera datasets that are being lost every year.

- Secure Australian data for the future with free unlimited image backups in the cloud

- Use AI to rapidly and accurately process images

- Provide upskilling training at key organisations and conferences; and

- Collate, curate, and share a world-first continental database via TERN and a user-friendly online dashboard to enable researchers and land managers Australia-wide to explore prior projects, register new projects, and freely access all data and infrastructure, with support to easily run robust analyses.

“If our mission is to improve conservation efforts, WildObs can provide the infrastructure to answer hundreds of research questions. WildObs can deliver stronger evidence to influence policies and management decisions and reduce redundancy in expensive sampling efforts. However, an observatory of this type requires us as researchers and land managers to put national interests ahead of our own, and put aside the traditional paradigm of data ownership: our data and technology must be open and freely available for everyone ”.

Dr Matthew Luskin, University of Queensland