More than a decade of ecosystem measurements in Australia’s Red Centre are providing an unprecedented understanding of the health and function of Australia’s vast arid ecosystems. The data tell a tale of a tough life in the desert, with highly variable rainfall patterns and carbon dynamics, but of which, thanks to research infrastructure investments, Australia’s scientists are developing an intimate understanding.

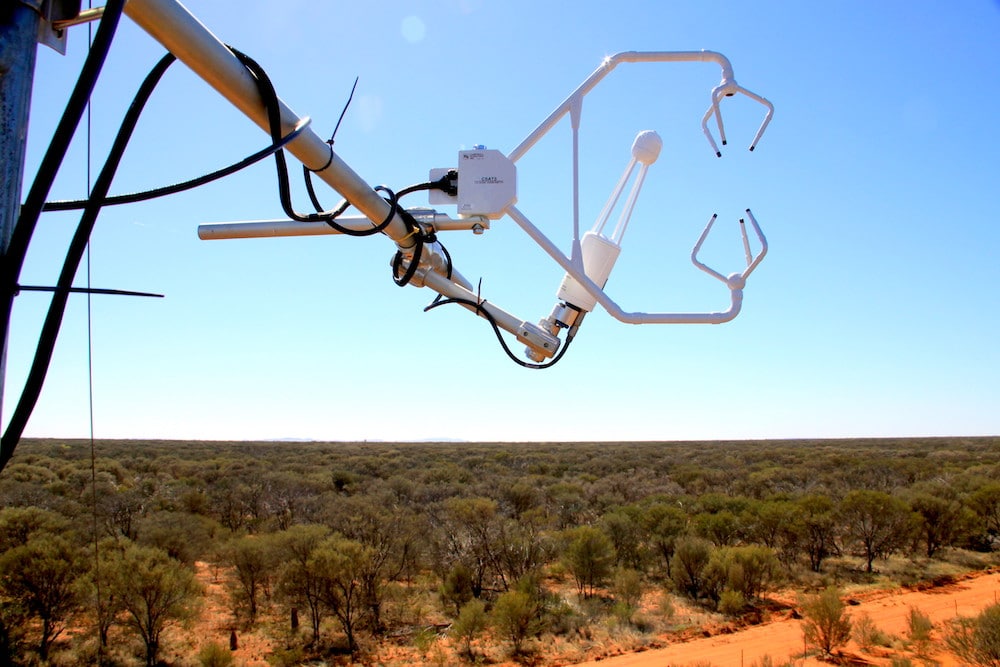

TERN’s Alice Mulga SuperSite, and its paired OzFlux site Ti Tree East, provide crucial data on the land-atmosphere exchanges of carbon, water and energy in the dryland arid and semi-arid ecosystems that dominate the interior of Australia. Established in 2010 and equipped with autonomous sensors that measure the pulse of the ecosystem 24/7, the two Northern Territory sites deliver open-access, high-temporal-resolution, long-term data to all interested researchers.

Over 10 years of measurements at the sites have yielded more than 100 publications between the two sites (Alice Mulga Google Scholar & Ti Tree East Google Scholar), their value to the Australian and international research communities is enormous.

From assessing the seasonal patterns of carbon and water flux to rainfall pulses in Acacia -dominated savannas, to enhancing our technical understanding of component carbon fluxes, and understanding the impact of interacting climate modes that can lead to large contrasts in inter-annual carbon uptake, observations from these two sites have revealed a wealth of information about how climate has shaped, and continues to alter, these ecosystems.

The eddy-covariance flux tower at the TERN Alice Mulga SuperSite (top) and a top of canopy view from the Ti Tree East flux tower (above) (credit: Jamie Cleverly)

Two towers tell the tale of life in the desert

The two sites are located on the Pine Hill cattle station, approximately 200 km north of Alice Springs in the Northern Territory. Their vegetation is predominantly the iconic Mulga (Acacia aneura) and hummock grasslands (Triodia schinzii), which cover about 50% of Australia’s land area. A small amount of grazing occurs at the Alice Mulga SuperSite, which is dominated by Mulga (Acacia aneura). In contrast, the Ti Tree East site experiences very little to no cattle grazing due to its unpalatable hummock grasses surrounding its small Mulga ‘patch’.

The two sites are managed by TERN’s Dr Jamie Cleverly from The University of Technology Sydney, who is also Associate Director of the OzFlux ecosystem research network.

“The water table at the TERN Alice Mulga SuperSite, which was established in 2010, is quite deep compared with the nearby Ti Tree East site—49 m compared with 8 m. It’s this contrast that led to the establishment of the Ti Tree East site in 2012 as part of the NCRIS-enabled Groundwater initiative, as it was surmised the site vegetation may have access to this groundwater.

However, it was later found that the Mulga patches are isolated from groundwater by a hardpan, whilst the widely spaced bloodwood trees use groundwater only in those brief periods when the air isn’t too hot and dry, just after rainstorms.”

Dr Jamie Cleverly, The University of Technology Sydney

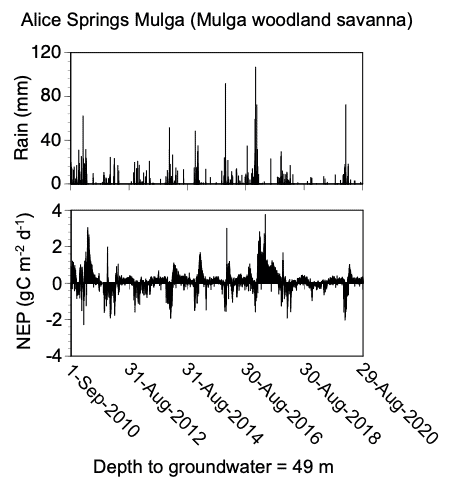

Annual precipitation at the site is typically low (around 300 mm per year), but can be highly variable, ranging from 54 mm recorded in 2019 to 750 mm in 2010.

This highly dynamic nature of rainfall extremes and the length of time between ‘drinks’ leads to extraordinary variations of carbon flux in these ecosystems. This dynamic was most pronounced during the strong La Nina event of 2011, where higher than average rainfall caused a greening of the southern hemisphere, and central Australia in particular.

The data collection instruments at the Alice Mulga SuperSite successfully recorded this dramatic increase in ecosystem productivity, facilitating an in-depth analysis of its impact. Similarly, record-breaking rainfall fell in January 2017, when more than 350 mm fell in a single month, and ecosystem productivity exceeded that of the 2011 land carbon uptake sink.

These sites have given researchers the unprecedented opportunity to observe and study the incredible ability of Australian vegetation to come alive with flooding rains.

Net ecosystem productivity (NEP) and rainfall across the 10-year measurement period from the Alice Mulga SuperSite. Negative fluxes represent loss from the ecosystem due to respiration and degradation, and positive fluxes represent carbon uptake into the system through photosynthesis. (Credit: Jamie Cleverly).

The harsh reality of desert life in the future

Periodic drought is a reality these ecosystems face in the semi-arid interior of Australia. Despite the greening pulses of 2011 and 2017, ecosystem productivity was relatively short lived due to a drought event that closely followed them.

In 2019, the hottest year on record in Australia, these ecosystems were pushed to their brink. The Alice Mulga SuperSite received much lower than average rainfall from April 2017 through to the end of 2019—representing the latest big drought of the region.

In August 2020, TERN’s Ecosystem Observation field team conducted detailed surveys and sampling at the Alice Mulga SuperSite and at tens of other sites in the Northern Territory. Early anecdotal reports from the TERN’s Field Lead and Senior Botanist, Emrys Leitch, indicate large swathes of Mulga die-back across the region—colloquially referring to it as a ‘mulgapocalypse’.

Dr Cleverly recalls a similar Mulga die back event during the 2012-2013 drought, with the return of significant rainfall to the area revitalising vegetation at both sites.

“With this current ‘mulgapocalypse’, up to half of the ‘dead’ trees could be zombies, waiting until favourable conditions to revive”

Dr Jamie Cleverly, The University of Technology Sydney

The data and samples collected during the winter 2020 TERN field survey campaign, are currently being curated and will be publicly released via TERN in the coming weeks. The data, samples and photographs from the campaign are expected to enable significant ongoing research into the observed Mulga dieback event.

The research being enabled by such surveys combined with the comprehensive long-term data records from the two flux monitoring sites are critical in understanding the harsh reality of desert life now and in the future.

While the research continues, we patiently wait and hope for much needed rain to return and bring these trees back to life. With La Niña and a negative Indian Ocean dipole looking likely, all fingers are crossed for another big wet in the coming months.